The Importance of Art in Understanding Technology

Originally published on mirror.xyz 17 November, 2025.

In this text, I argue that art can play an important role in understanding a technological world. I intended to spell out this argument after realizing that I learned a lot about digital technology by exploring art made with this medium. In addition, people grappling with the digital art practice regularly provide me with thought-provoking insights. A recent example of the latter was the presentation of Mitchell F. Chan, also a creator of digital art himself, at the 2024 Art Blocks Marfa weekend: What Do You Do After You Change the World? Therein Chan proposes a model for art and “modernism”. The crucial element unifying modernist art proves to be an interesting instrument for understanding technology.

Chan's art model

In a conceptual way, a model is an informative representation of reality with the purpose of better understanding it. I will use Chan’s model to understand art, good art and modernist art. This differs from theories claiming to explain art as a (natural) phenomenon and definitions postulating necessary and sufficient conditions for art.

Art is about something

Chan starts off with intuitively claiming that art needs to be about something. Although the opposite might not be unfeasible, i.e. making art (as much as possible) about nothing, people tend to project their own meaning into such art. This indicates how much people need an artwork to be about something.

Good art allows you to travel conceptually

To make good art, however, it does not suffice to be merely about something. Chan argues that the conceptual distance, an artwork allows you to travel, determines the quality of the art. The most simple and obvious way to organize such a distance is by creating an artwork about (at least) two things, ideas, concepts, … Less straightforwardly, artists can create an artwork about one thing and use a circle as a pattern to organize a conceptual distance.

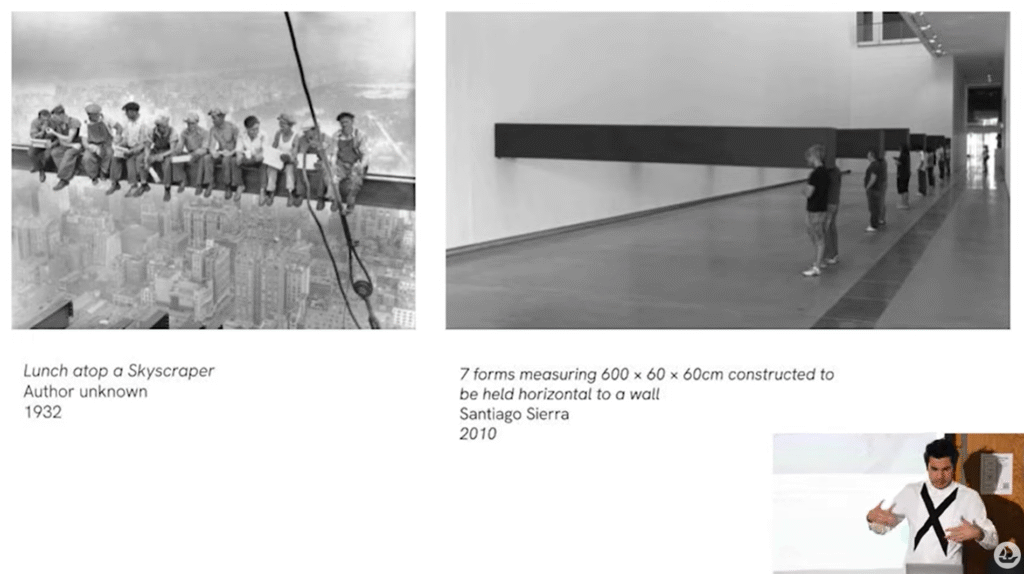

Chan provides an example of establishing (the lack of) a conceptual distance between two things by imagery of people and beams. The iconic photograph Lunch Atop a Skyscraper, taken in New York city in 1932, has a significant message to tell, namely one of hope for better economic times and immigrant workers’ contribution. There is, however, no such conceptual distance to travel as in Santiago Sierra’s 2010 artwork 7 Forms Measuring 600 × 60 × 60cm Constructed to Be Held Horizontal to a Wall. This artwork consists of beams and people as well, but it is no construction site because the latter support the former. The participants were unemployed, but received a minimum wage for performing this useless task, simultaneously being exploited and compensated. When processing whatever this artwork can be about, you are taken onto a conceptual journey travelling between these things.

“The greatest amount of distance that you can make a viewer travel between those two things that an artwork may be about, while still maintaining credibility, that is to say while never being specious, hyperbolic or dubious . . . is a reasonable indicator of whether you are looking at a good artwork.” (by Chan)

Good art can be about one thing

What does it mean to organize a conceptual distance within an artwork by deploying one thing, idea, concept, … and a circle? The artist can achieve this by making art about the art itself. So, the subject of an artwork is about the object containing it. The content is about its form. The message is the medium. It is art about the material or process that realizes it. This equating of medium and message in an artwork can be conceived as travelling a conceptual distance along a circle: moving from its content, through its form and back to its content.

Is this a remarkable feature of modern art? On the one hand, it is a priori possible that art can be about its medium and it could therefore occasionally happen. On the other hand, however, Chan argues that the modernist art formula of the twentieth century boils down to art exploring its medium. He acknowledges though that this is an oversimplification of modern art and elsewhere seems to suggest it is more precise to refer to “formalism” rather than modernism in this respect.

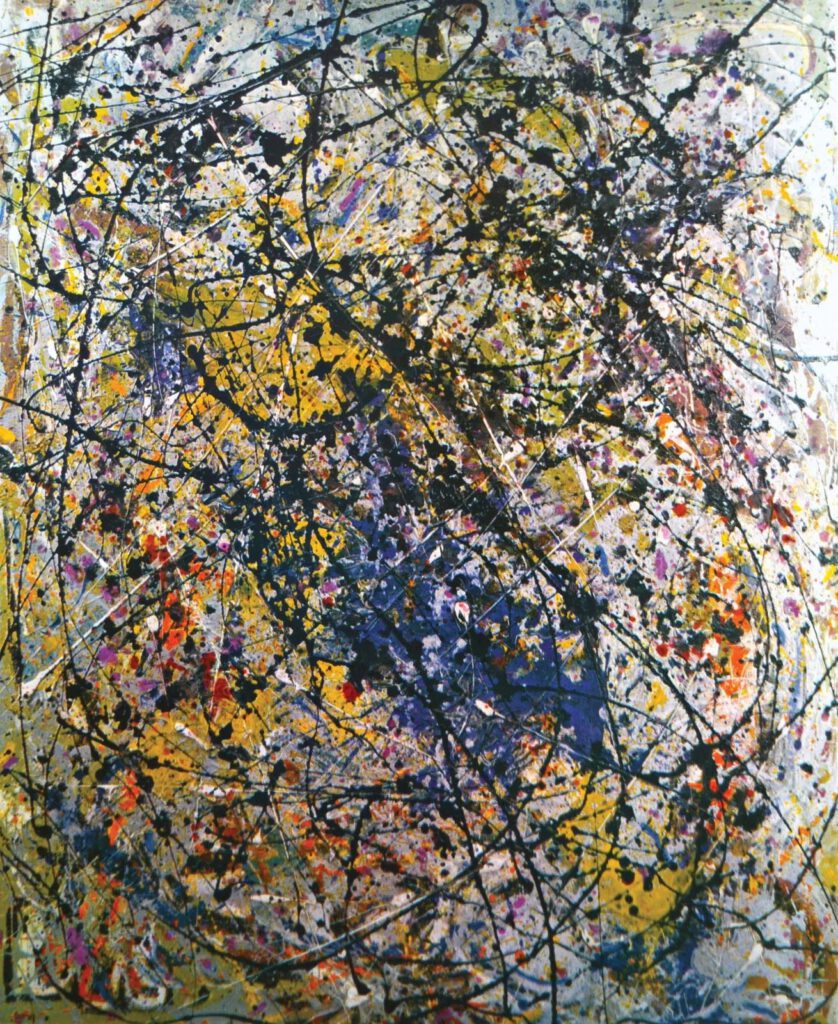

Some art movements of this time fit the formula better than others. Surrealism mainly examines the contents of the unconscious mind and not so much its medium. Cubism and abstract expressionism do focus on form. Art critic Clement Greenberg saw in the former an exploration of the two-dimensional flatness of the canvas, a defining characteristic of the medium. The latter he deemed the culmination of the self-analysis of paint(ing). Greenberg championed Jackson Pollock who, according to Chan, illustrated as nakedly and didactically as possible the process of his art’s creation, i.e. painting, or the characteristics of the used material, i.e. paint.

“You choose a medium. Medium is the message. You play that note really high and then the object you create becomes a diagram of its own creation. That’s the formula, baby!” (by Chan)

Technological formalism

Paint(ing) as an artistic medium does not matter much to most people or to the way society works. Technology shapes our lives and permeates the social fabric. It is therefore worthy of elaborate critical exploration from all possible vantage points. Formalist technological art offers an unconventional route towards a better comprehension of technology. It functions, according to Chan, as an aesthetic way of understanding a technological world and as an application of special interest of the twentieth century modernist formula.

As outlined above, technological formalism is, on the one hand, the continuation of the modernist art formula because of “archaeological” reasoning – explaining something regressively referencing to its origin. On the other hand, technological formalism’s prevalence follows from “teleological” reasoning – explaining something progressively referencing to its end – due to a particular challenge for art made with technology.

The challenge for technological art

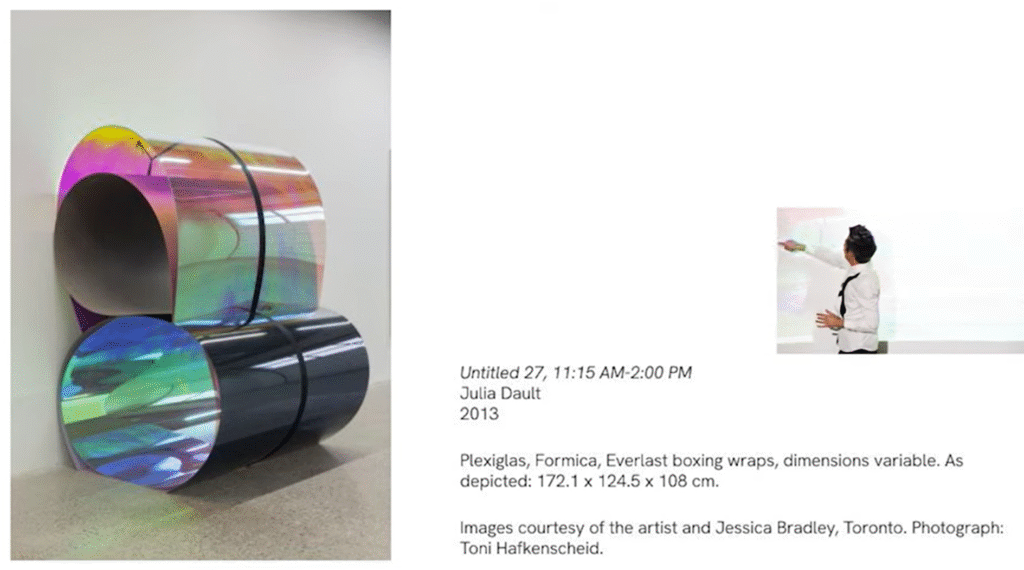

Technological art faces a particular challenge because of its innovation, novelty, gadgetness, … that is not always present in other formalist art. For instance, Julia Dault’s sculptures from plexiglass are made of unconventional materials in an art context, but the capacities of the medium, such as flexibility and transparency, are part of our common knowledge. A new technology, on the contrary, is originally not understood by the general (art) public, which makes people focus on the technology. More time is spent on the technological substrate detracting attention from the content. Technology overshadows and dominates any other message.

Because of this illiteracy concerning a new medium, the potential audience for art is unlikely to accurately appraise art made with technology. For those who don’t strive to make good art, this is less of an issue because they could benefit from the situation. The use of technology as a medium obfuscates and can consequentially function like a smoke screen to hide the lack of an interesting message. However, artists striving to make good art by establishing a conceptual distance want their work to be properly understood and appraised. This leads, among other things, to appreciating its message or correctly distinguishing good from bad art.

The solution(s)

Chan proposes three solutions to tackle this challenge. First, making technology invisible facilitates better art appraisals but it is insufficient to fully compensate for medium illiteracy. Second, targeting a subculture with a specialized education background enables accurate appraisals, but it remains a narrow audience somewhat isolated from the rest of society. The third solution is technological formalism. Rather than alleviating the symptoms or consequences, like the first and second solution do, it directly tackles the underlying problem or cause at hand, namely medium illiteracy.

If art struggles to contain any other message than its medium, because of the novelty of the technology used, artists can turn the medium into the message and explore the medium as part of the art content. They can exploit the inevitable focus on the technological substrate of their art in order to illuminate it. Chan proposes that in this way technology can be rigorously examined and explained through artworks. Figuratively speaking, medium and message are tightly knotted together, but with a long loop connecting them, which simultaneously represents a didactic journey and conceptual distance to travel.

“Technology has a unique challenge in containing meaning, so too does it have a unique superpower . . . Technology casts a pervasive and imposing shadow over the artwork, but . . . when we are attuned to what it represents in a social context, then digital art sort of comes with a subject matter baked right in.” (by Chan)

These things place technological formalism at a remarkable crossroads or sweet spot. It currently is able to receive accurate appraisals because it equates medium with message. Aspiring to make good formalist art, installing a conceptual distance, is aligned with fostering medium literacy. This improves accurate appraisals of other (than formalist) technological art in the future and enables artists to explore whatever this medium has to offer.

Chan illustrates this last point by referring to the film Arrival of a Train at la Ciotat, a production from 1896 by Auguste and Louis Lumière. According to myth people were terrified and ran out of the theater when they saw a train moving toward them on the cinema screen. The audience at that time did not understand the new medium enough and was therefore too preoccupied with its novelty so that the message would not have reached them. A little later though when the public was accustomed to the technology, film makers could successfully communicate stories with a plot and characters, such as in Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery from 1903.

“When you get to the point that the technology is invisible . . . you can actually fully exploit all the potential of your medium and . . . you can tell the kind of stories that are only possible through your medium . . . It happened with cinema, photography, video games and it is going to happen in AI . . . No medium gets a direct route to this point of global understanding and normalization.” (by Chan)

Examples

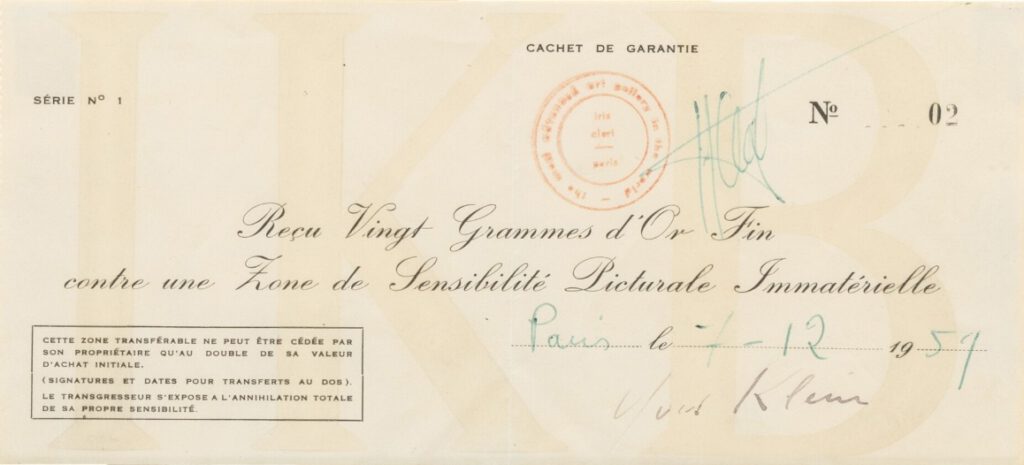

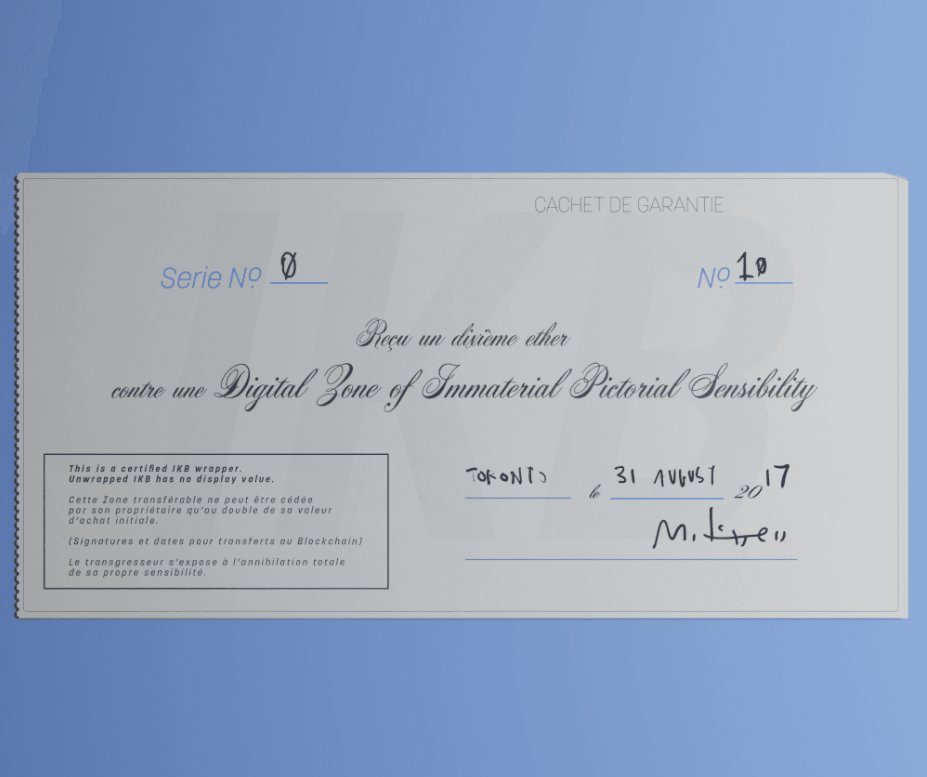

Remarkably suited to illustrate contemporary technological formalism is Chan’s 2017 artwork Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility , accompanied by the explanatory Blue Paper. It is a digital reproduction and update of the artwork Zones de Sensibilité Picturale Immatérielleconceived by Yves Klein in 1958. Klein’s artwork itself is an empty space imbued with the sensibility of his patented color International Klein Blue (IKB). Strikingly, you could purchase this immaterial art with gold and receive a paper certificate as proof of the transaction.

Chan realizes that Klein’s immaterial zones deliver an interesting perspective on the new medium of blockchain technology. In their likeness, Klein’s work legitimizes Chan’s. What Klein does, among other things, is simultaneously separating and connecting (the ownership of) the artistic thing and the certificate pointing to the thing. This practice, common for conceptual art, turned out to be the prototype of the current blockchain ownership model. Here, smart contracts define (non-fungible) tokens (NFTs), functioning as certificates that correspond to art.

“Just a few years ago the idea of buying and selling certificates for immaterial artworks was not common. It required the legitimizing callback to conceptual forebears like Klein, along with lengthy explanations. Chan’s NFTification of Klein’s famous work almost seems obvious in retrospect, but perhaps that’s because it was essential, or inevitable. The design of the Ethereum network, with its ability to exchange contracts that attest to the value and ownership of non-objects, already echoed Klein’s receipts. Chan made the connection explicit.” (from Mitchell F. Chan – Gaming the System by Kevin Buist)

In their contrast, Chan’s art advances upon Klein’s notions of immaterial culture. Klein contended (invisible) IKB blue occupied a finite physical space in an art gallery, while Chan imbued a digital space, as a blank webpage, by (a different shade of) blue. In addition to pushing the artistic thing further along the spectrum of immateriality, Chan dematerializes the transactional element using a blockchain token as a digital certificate, instead of some paper. This token is not completely immaterial, however, because the software expressing it reduces abstractly to binary computer bits physically realized in hardware states. Unlike regular software stored on one computer, software on a blockchain like Ethereum is stored on (a network of) many. This makes the token less reliant on hardware states at a particular location controlled by some intermediary (the digital exhibition space was also originally stored in a distributed way with Swarm). Such architecturally and politically decentralized storage delocalizes the art certificate and unties it from any specific material.

Chan’s rigorous formalist exploration of blockchain as a medium is not an isolated instance. With extraordinary foresight in this respect operated the artist Rhea Myers. As early as 2014, she was writing artistic code for Ethereum, before the launch of (a public testnet of) the protocol. Her art project Is Art , in particular, consists of smart contract code asserting that it is art (or not) and its artistic state can be toggled when instructed to do so. It is formalist because it combines the ideas of the dematerialization of conceptual art, the “Duchampian aesthetic transubstantiation of artistic nomination” and the interactivity of net.art to showcase characteristics central to blockchain. Also around that time and equally important, Myers demonstrated ways to store and own art by means of blockchain in her blog post Artworld Ethereum – Identity, Ownership and Authenticity. Both her art and writing strengthen each other and together prove effective to better understand blockchain as a medium.

“Myers takes a different approach. She sees in the blockchain a technology . . . and the only way to truly understand the implications of this development, for better or worse, is to play them out.” (from Rhea Myers – Conceptualism Rehashed by Kevin Buist)

Beyond technological formalism

The broader art world plays a not to be ignored role in educating about new media used in art creation. This profane interpretation of the concept “art world” refers to all the actors at work in art – unlike Arthur Danto’s spiritual “artworld” as an “atmosphere of art theory”. The usual inhabitants of the art world also operate in its subsection specifically interest in technology: artists, collectors, art galleries, auction houses, museums, … In addition, actors originally not associated with art can enter this network of people from their own angle, such as technologists and entrepreneurs. What they all have in common is a penchant to grapple with technology as a new medium for (artistic) human expression. In a communal effort they consider technology’s impact on and entanglement with society.

To support this claim, I present a brief anthology. The critical essays of Right Click Save intend “to make sense of the hybrid realities where analog and digital, and human and nonhuman intersect”. Art institution Le Random educates with its elaborate generative art timeline , which includes many related historic events and developments. The Toledo Museum of Art shows with their exhibition Infinite Images the art of algorithms and interprets the evolution of computer-generated media through a series of essays. Contemporary art gallery Fellowship offers a curatorial program for artists using technology as a medium and it strives to contextualize their practice adequately. Auction house Christie’s helps their customer base to understand code-based creativity. The pseudonymous collector Jediwolf aims to illuminate the “journey to the AI world we live in today” with the digital exhibition of its UnderTheGAN collection. Technologist and entrepreneur Jacob Horne describes that “cryptomedia” makes hypermedia ownable. Artist Matt Dryhurst lays out how this new kind of ownership enables fairly compensated, free digital media. All together and in their diverse ways, these actors contribute to a pluralistic interpretation of (the societal role of) technology.

Conclusion

I wrote this text to argue that art plays an important role in understanding technology. Chan’s art model proved insightful and useful. It explains how (good) art can ingeniously be about itself, equating medium and message. If this modernist art formula is applied to new technology, it fosters understanding of this medium. Such formalism solves a particular challenge for technological art, that technology as a medium initially overshadows any other message in art. These reasons combine to justify and boost the prevalence of technological formalism, turning it into an interesting, aesthetic route to explore technology.

The opposite can happen too: technology or tools introduced in an art context can help to better understand art. Klein and Chan demonstrated that the financial, assetlike component of art can be separated from the artistic thing itself by means of a paper or blockchain certificate. The digital revolution unveils that (some) art can be represented as information, driving a wedge between art and its carrier, instead of being closely tied to and embodied by material. Art made by increasingly autonomous systems – starting with simple instructions like Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings, moving through forged computer algorithms and culminating into AI models and agents – questions the role of (human) agency in creating it. These developments disassemble the bundle of ideas typically held together within the practice of art creation, such as object, artistic thing, artist and ownership.

More generally speaking, art can be important in understanding the world, especially the human (made) part of it, for example about intersubjective realities organizing society. While art was never devoid of ideas, further distancing from its mimetic function, it evolved into a more conceptual undertaking during the twentieth century. Grappling with this contemporary, less conventional art tends towards the practice of understanding philosophical theories, mainly in the continental tradition. As such, it takes substantial mental effort to make intelligible and might be far from factual, but it enriches our reality significantly…